Position Paper of Faculty Members of the University of the Philippines Population Institute on the proposed

“Prevention of Adolescent Pregnancy Act of 2022”

07 February 2023

The undersigned faculty members of the University of the Philippines Population Institute (UPPI) thank the Senate Committees on Women, Children, Family Relations & Gender Equality, Social Justice, Welfare and Rural Development, Health and Demography, and Finance, for the invitation to comment on the bills that seek to address the problem of teenage or adolescent pregnancy in the country.

UPPI has been at the forefront of tracking and analyzing demographic phenomena such as fertility, mortality, migration, and changing age structure. Since 1982, the Institute conducted the Young Adult Fertility and Sexuality Survey, also known as the YAFS. From the initial goal of understanding fertility patterns and behavior of young Filipino women aged 15-24, the survey has since expanded to include young men and covers wide-ranging topics that affect the sexual health and fertility concerns of young people in the country. UPPI and the Demographic Research and Development Foundation (DRDF) have conducted five rounds of YAFS for the past four decades (i.e., 1982, 1994, 2002, 2013, and 2021).

Teenage pregnancy and teenage births are two of the indicators that YAFS has tracked through the years because of their important social implications. We define teenage pregnancy as pregnancy occurring in women aged 15–19. This is measured based on reported birth histories which include information on each pregnancy – dates, outcomes (miscarriage, stillborn, live birth), attempts at prematurely ending the pregnancy, and survival status. Only pregnancies resulting in live births are considered in measuring teen fertility.

UPPI shares in the multi-sectoral efforts to address this issue, and we are happy that the data being generated by our research, as well as the analyses based on other data sources that we are doing in the Institute, are being used as inputs for policies and programs that will promote the well-being and development of Filipino young people.

What do the data say about teenage pregnancy in the Philippines?

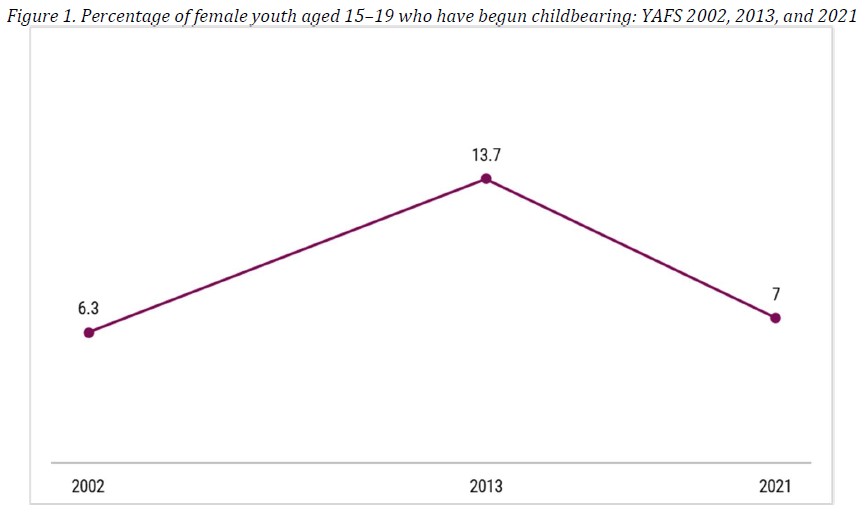

Based on the series of YAFS surveys, we observed an increase in the prevalence of teenage motherhood between 2002 and 2013, from 6.3% to 13.7%. However, in the recent 2021 YAFS, the percentage of young women 15–19 who have begun childbearing dropped to 7%.

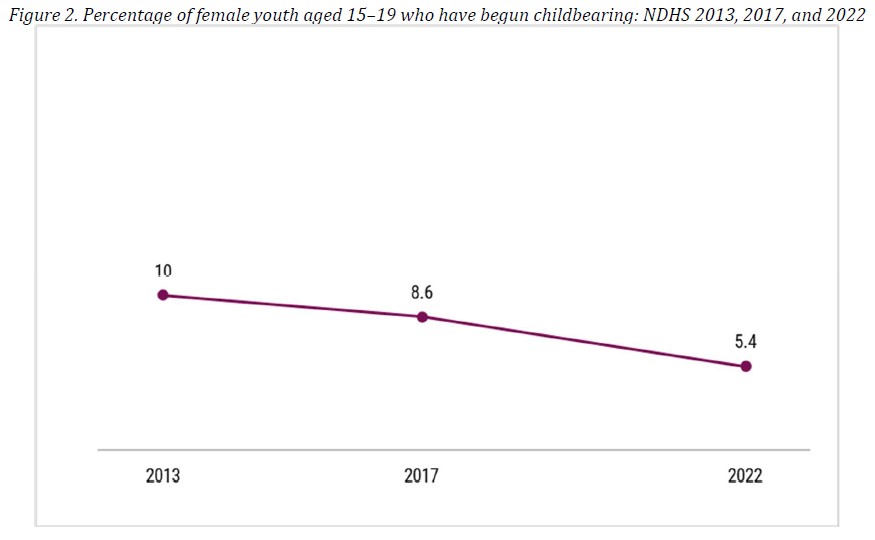

The National Demographic and Health Survey (NDHS) corroborated this result. There was already a declining trend in the percentage of 15–19 who have begun childbearing since 2013. In the 2013 NDHS, 10% of 15–19 reported to having begun childbearing; this dropped to 8.6% in 2017 and to 5.4% in 2022.

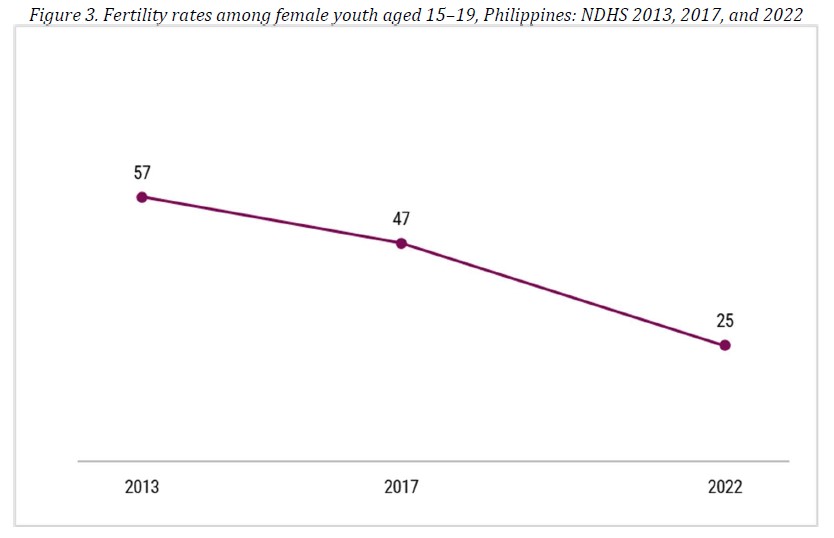

Similarly, the teen birth rate or the number of live births per 1,000 teen girls aged 15–19 based on the 2022 NDHS also decreased to 25 from 47 in 2017.

What about births among women under the age of 15?

Much has been said about the increasing number of young girls 10–14 who have become pregnant.

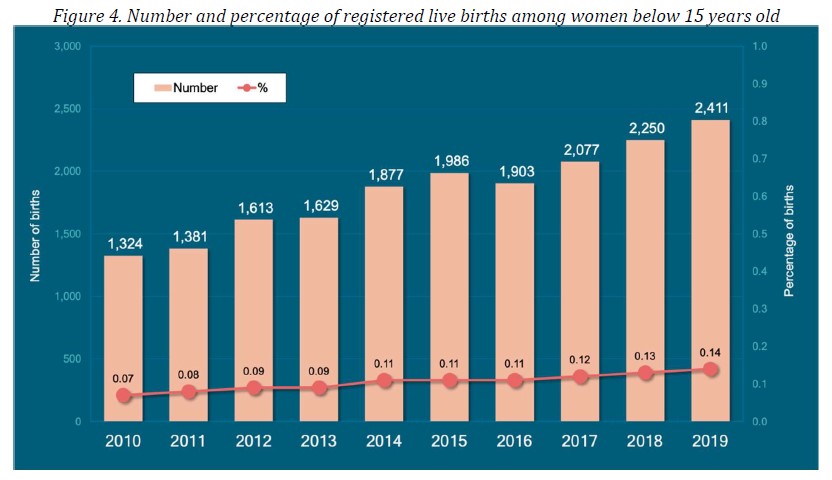

Our analysis of the civil registration and vital statistics data from 2010 to 2019 points to an increasing number of births from young women under age of 15: from 1,324 reported in 2010 to 2,411 in 2019. In terms of percentage, this is equivalent to 0.07% and 0.14% of live births in 2010 and 2019, respectively. The increasing number of births from this young cohort can be partly attributed to the increasing population base of women in this age cohort. We agree, however, that regardless of whether the number increases or the percentage remains stable over time, the fact that this is happening to our young girls is a cause of concern. There should be no pregnancy among girls age 10-14.

But in our efforts to bring to light this important issue, let us use data responsibly. If we look at the trends from both national surveys and civil registration statistics, they all point to a declining percentage of teen pregnancy, either from the age group 15–19 or from 10- 17. This is important to point out because teenage pregnancy is not a new issue. The current trend also implies that some programs in place might be working. We need to know what programs work and how they can be further improved, for example, the Responsible Parenthood and Reproductive Health (RPRH) Law (RA No. 10354) and the K- 12 program, which extends schooling for young girls and, in the process, provides them with better opportunities for education and employment.

Aside from the decrease in the prevalence of early childbearing, results of the 2021 YAFS also show a lower percentage of young people who engaged in early sexual activity, and sex outside marriage, from 32% in 2013 to 22% in 2021. Compared to previous YAFS rounds, in 2021, the majority of those with premarital sex experience reported using any form of protection during their first sexual experience, 68% for males and 57% for females. We also see a preference for smaller family sizes as indicated by the ideal number of children among our youth. Among males, the average number of children they prefer is 2.6, and for females, 2.2. This was down from 3.1 and 2.6 in 2002. Between 2013 and 2021, we also saw a slight decline in the percentage of unwanted, mistimed, and even intended first pregnancies. Among first-time mothers, 16.8% said their pregnancy was unwanted; in 2013, the percentage was 18. Similarly, 18.5% said the pregnancy was mistimed, down from 22.4% in 2013. The percentage of young girls who reported they did something to end a pregnancy early also declined from 12% in 2013 to 6% in 2021.

Two percent of women and 1.4% of men aged 18-24 experienced coercive sex by age 18. These were mostly perpetuated by their boyfriend/girlfriend and their friends.

Four in 10 young Filipinos said they did not have material sources of information about sex, and among those with material sources, the majority rely on social media. Compared to previous rounds, more young people now said they have no one to consult when they have questions about sex: 33% among men and 23% among women. It is also not common to discuss sex at home. Only 12-13% of young people said they discussed sex at home. Awareness and knowledge of HIV/AIDS were lower compared to previous surveys.

The fact that we conducted the survey during the pandemic may have implications on the results that we have seen. There was limited mobility because of the lockdown, thus, few opportunities for social activities among young people. Whether the trend we observed from the data will continue or will go back to the pre-pandemic level remains to be seen. But there are important findings that the proposed bills can address.

We support the provisions on the need for age and development-appropriate comprehensive sexuality education, both for in-school and out-of-school youth and parents of adolescents. This should also include the development of materials and their dissemination through platforms that are more accessible to young people.

Regarding social protection for adolescent mothers and fathers, while this is a good provision, it should also recognize the important role of the family. The Commission on Population and Development (POPCOM) estimated that over 133,000 families will be headed by minors by the end of 2021. However, adolescent parents do not form their own separate household; they remain with their parents and are fully supported by them as they raise their first child. There should be a provision that gives incentives to parents supporting their children who are teenage parents.

Finally, on the creation of a national information system on the prevention of adolescent pregnancy (Section 21), we support the institutionalization of the YAFS as a regular national survey to be funded by the government. However, we do not support extending the coverage to earlier ages, i.e., 10-14, of existing surveys such as the YAFS, NDHS, FHS, and Maternal and Child Health. Childbearing at ages 10-14 is still a rare event, and to include this in the said surveys will only complicate logistical arrangements because of research ethics and data privacy concerns when dealing with children.

---signed---

Christian Joy P. Cruz

Grace T. Cruz

J. Andres F. Ignacio

Vicente B. Jurlano

Maria Midea M. Kabamalan

Elma P. Laguna

Maria Paz N. Marquez

Nimfa B. Ogena

---

Download a PDF copy of the position paper here.

Share